Stopping Deep Sea Mining: Online tactics to thwart new extractivism

- Davin Hutchins

- Jan 5, 2023

- 8 min read

Updated: Dec 10, 2025

In 2022, I had the privilege of being assigned as a global campaign strategist and digital lead for a brand new crusade at Greenpeace - the Stop Deep Sea Mining campaign. This upstart initiative was an innovative idea pitched to our global program basket by campaigners in our US office in partnership with counterparts in our New Zealand office.

Originally a tactical component of our multi-year Protect The Oceans campaign in 2021, Stop Deep Sea Mining was spun-off because it had a different strategic focus than its forebearer. Protect The Oceans aimed to make millions of square kilometers of ocean off-limits to destructive industries by creating a network of sanctuaries through a strong Global Oceans Treaty. The main aim of Stop DSM was to convince corporate players in the electric vehicle market to never start dredging up minerals like cobalt, nickel, and manganese from the bottom of the ocean for rechargeable batteries.

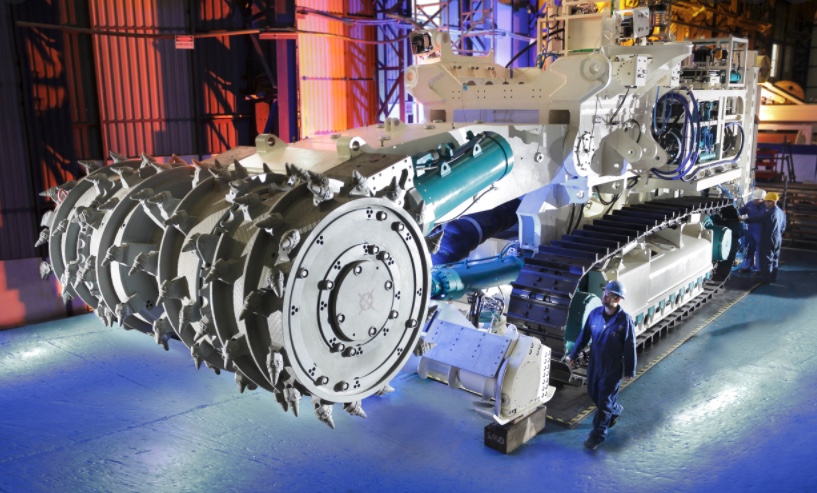

Established mining companies and startups like GSR Deme (Belgium) and The Metals Company (Canada) have been testing heavy machinery to collect polymetallic nodules from the ocean floor, pitching EV companies the need to mine the sea for the planet’s clean energy transition, claiming that deep-sea mining is a "battery in a rock" and their methods have the "lightest planetary touch."

But their methods include using machines that suck nodules from the ocean floor or pierce teeth-laden rotors on the ocean floor. Scientists warn that even a cautious approach to deep-sea mining could be absolutely devastating. Deep sea organisms are slow-growing and fragile, and therefore, much less likely to recover from disturbance. Deep sea habitats regenerate and grow incredibly slowly, requiring thousands, if not millions, of years to recover from any form of harm.

At the moment these companies' activities are restricted to limited testing because of the International Seabed Authority, a UN body headquartered in Jamaica, which is charged with writing international guidelines governing the deep sea. They have yet to author laws governing this future practice but they're facing pressure from both mining companies and some governments.

Private mining companies are promising small Pacific nations they could be on the ground floor of a new profitable industry, but in truth, mining companies have been manipulating power brokers behind the scenes. Pacific Peoples have not been consulted properly and have often been cut off from opaque negotiations.

The Clarion Clipperton Zone in the Pacific Ocean is where most of the initial explorations are taking place, far from the public eye. Here are a few photos the campaign compiled of the amazing organisms relying upon the deep-sea ecosystem.

We can meet the planet's growing needs through scaled-up battery and mineral recycling, a circular economy focused on reusability and technological advances that reduce dependency on mining minerals and increase the efficiency and longevity of batteries.

There are three key communications, digital and tactical components I'd like to share with readers that I think helped put this campaign on a stronger footing and helped it become a "global priority" campaign at Greenpeace:

an eye-popping visual IS

a web app to rank and engage automakers

a global survey to measure the public's gut reaction to this largely unseen industry.

Establishing Stop Deep Sea Mining's Visual ID

The two national campaign leads, Arlo and James, from the US and Aotearoa (New Zealand) respectively, definitely wanted a visual ID that captured the imagination of our target audiences while expressing components of a nascent industry the public probably knew nothing about.

Because the main focus of our first-year work was to get as many EV makers as possible to publicly distance themselves from deep sea mining, we felt the campaign brand had to appeal to EV executives, employees, and enthusiasts by being hopeful, optimistic, and a bit futuristic. But from the native Pacific People's perspective, who are often skeptical of techno-fixes to address planetary harm, we needed to convey ancient wisdom and reverence for the planet and ocean. Third, we needed to convey mystery and wonderment for deep-sea life we barely understand. Greenpeace conducted a global audience survey in 2020 and reverence for the ocean and its protection is one of the most resonant frames.

I recruited Paul, a designer I worked on for a carbon offsets project called Real Zero a few months prior. After introducing Paul to Arlo and James and agreeing on general concepts, Paul got to work bringing our ideas to life. The signature logo we landed on made use of deep blues with a bold colorful font and motifs actually derived from (not appropriated from) Pacific activists James had been working with.

My favorite use of the visual ID was in a few billboards we bought on the road from the Kingston Airport to the International Seabed Authority, to make sure every negotiator knew this was becoming a hot-button, public issue.

At first, we weren't even sure of the campaign's official name and hashtag but we landed on #StopDeepSeaMining as it was straightforward and used sparingly among deep-sea coalitions and experts. In less than a year, this logo, related social media, and protest banners became the touchstone to Stop Deep Sea Mining efforts all over the internet and the world.

Using the media analysis tool Talkwalker, we detected 1,400 articles and social media posts in 2022, a huge jump from 2021 where coverage was intermittent. We also measured two narratives - deep sea mining as a clean energy solution and deep sea mining as causing ecosystem damage. When we measured, nearly 90% of the articles reflected the damage narrative. Greenpeace Instagram posts were consistently the posts with the highest engagement across any media, helping us set this skeptical tone.

Only 10% of the media items reflected the halcyon claims of The Metals Company. Once the honest press stories began emerging, the narrative from The Metals Company came to a near standstill at the beginning of 2022 after its bad press and financial woes.

Helping EV makers Race To The Top

Soon after, Arlo, James, and I toyed with the concept of creating a digital campaign tool that could rank name-brand EV makers based on their position in deep-sea mining. We also wanted a way to use public pressure to make the laggards move. The plan was to rank companies according to varying criteria: a business statement opposing DSM, support of a global moratorium, commitment to recycling battery minerals, and labor rights. When criteria would change, the ranking position of their marker would be higher. We liked the hashtag "RaceToTheTop" as this would be an encouragement campaign, not a shaming exercise.

Since the primary targets were auto companies, we thought about some sort of race with cars being the markers. At first, we thought an aerial view of cars racing to the ocean shore. Then we thought maybe the cars would be racing up a mountain. We struggled with the best analog that captured racing and the ocean's mystery but luckily, we hired an innovative webshop based in Auckland called Gravitate. Project lead Manu digested our general idea and assimilated Paul's brand ID and took it to his team.

The concept we collaboratively landed on was that users would enter the web app on the surface of the ocean where things appear serene and harmless. By clicking a button, they would dive to the darker ocean floor, passing familiar auto brands and sea creatures on their way down to witness "the monster:" heavy deep-sea machinery.

At the ocean floor, users would begin learning about deep-sea mining issues through pop-up boxes. As they "swim" toward the surface, they pass mysterious deep sea creatures and familiar auto brands like Ford, GM, Tesla, Volkswagen, BMW, etc. The auto brands that earned the most favorable criteria "raced to the top" and appeared nearer to the surface. The better the ranking, the further the brands were from the sea monster at the bottom of the ocean.

In addition to ranking the brands, we wanted the app users to engage with the brands on Twitter. So by clicking on a logo, the company's ranking and our criteria were fully explained. Then, users could also Tweet at the brands urging them to make a further commitment.

In its first month, the web app generated more than a thousand tweets at target companies. Five brands - Volkswagen, Renault, BMW, Rivian, and Volvo - came out formally in support of a worldwide moratorium on deep-sea mining which was our highest ask. Ford, GM, and Tesla did become members of the Initiative for Responsible Mining Assurance (IRMA), a multi-stakeholder organization that assesses mines against its Standard for Responsible Mining. IRMA does not allow the use of its standard to score deep-sea mining operations.

Measuring public opinion on deep-sea mining

One thing we never gathered solid data on was how the public felt about deep-sea mining specifically. Greenpeace had been asking about ocean priorities from its core supporters for years but not concerning an industry so new. Good audience data leads to better campaigning, messaging, and objective setting in my experience.

Using a similar method I devised for our Real Zero audience polling, I designed a simple survey that was deployed through Greenpeace mailing lists and social media channels using the Typeform survey platform, with our offices in the U.S., Aotearoa, France, Germany, Norway, and Denmark actively participating. In the two-week survey, more than 15,000 people participated.

One challenge I had is that the survey had to be conducted in nine languages, English, Spanish, French, German, Portuguese, Danish, Norwegian, Finnish, and Chinese. So I ended up with 15,000 lines of data all randomized in different languages which I found was also too big for Google Sheets to sort and filter.

Using some improvised data-cleaning skills I had gained over the years, I managed to get all of the data in a format for analysis. In short, I followed these steps:

Combined all of the multi-lingual raw data spreadsheets (.xls) from each office survey.

Sorted the data by language and aligned the columns.

Separated each language block into a separate spreadsheet.

Mass-translated each .xls file into English using Google Translate (yes this actually works with big data!)

Recombined all of the translated data into a single English data set in Excel

Created visualizations and analysis.

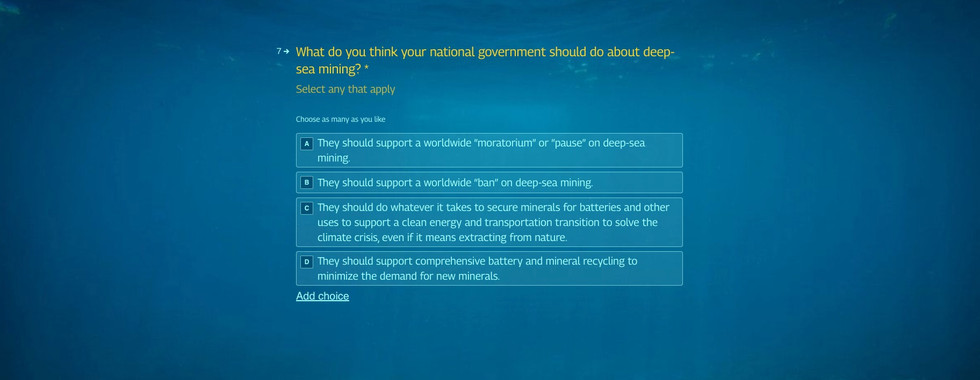

The public answered more or less in line with the aims of our campaign. When asked about what their government should to regarding deep-sea mining:

68.2% answered: “My government should support a worldwide ban on deep-sea mining.”

34.7% answered: “My government should support a worldwide moratorium or pause on deep-sea mining.”

When asked, “What actions would you be willing to take personally to stop deep sea mining before it begins?"

91.3% answered: I would sign a petition supporting a global moratorium or ban on deep-sea mining.

36.9% answered: I would participate in a protest or action directed toward my government in support of a deep-sea mining moratorium or ban.

Heading into Year Two

Greenpeace is investing more heavily in the campaign for its second year. In addition to our US and Aotearoa offices, our French and German offices are contributing time and resources. Our goal is to build a critical mass for a global moratorium and to bring mining negotiations and limited licenses to a standstill.

The governments of New Zealand and France have come out officially against deep-sea mining and we anticipate more. 227 parliament members from 50 different countries have signed on to a moratorium. In addition, Palau, Fiji, Samoa, and Micronesia have launched and Pacific nation anti-DSM alliance. As of this writing, The Metals Company, which surprisingly went public under a SPAC, has seen its share price consistently under $1.

Not too shabby for a year's work. Congrats to everyone who made it happen.

Comments